|

| Wrap it up and put a bow on it. Photo courtesy of Lance McCord |

Sometimes I love the Internet.

How else could I stumble across a 1960s report from the University of Tennessee detailing the results of years of trials into hedging experiments with popular landscape plants.

Much of the report is still useful today, nearly 50 years from when it was first published.

I learned that Abelia x grandiflora (still very much in use today) and Spiraea thunbergii (fallen out of favor) showed no ill effects from a 7-week drought.

On the other hand, ornamental quince (Chaenomeles) was nearly completely defoliated by the drought, which is interesting since numerous sources list Chaenomeles as being drought tolerant.

(Of course, the report does not say - as far as I could tell - whether the Chaenomeles was permanently damaged or only temporarily set back by the drought. Some gardeners might be willing to accept a temporary defoliation is the plant is just trying to prevent water loss (transpiration) from its leaves, but if it will leaf out again once the drought passes or in the spring...)

|

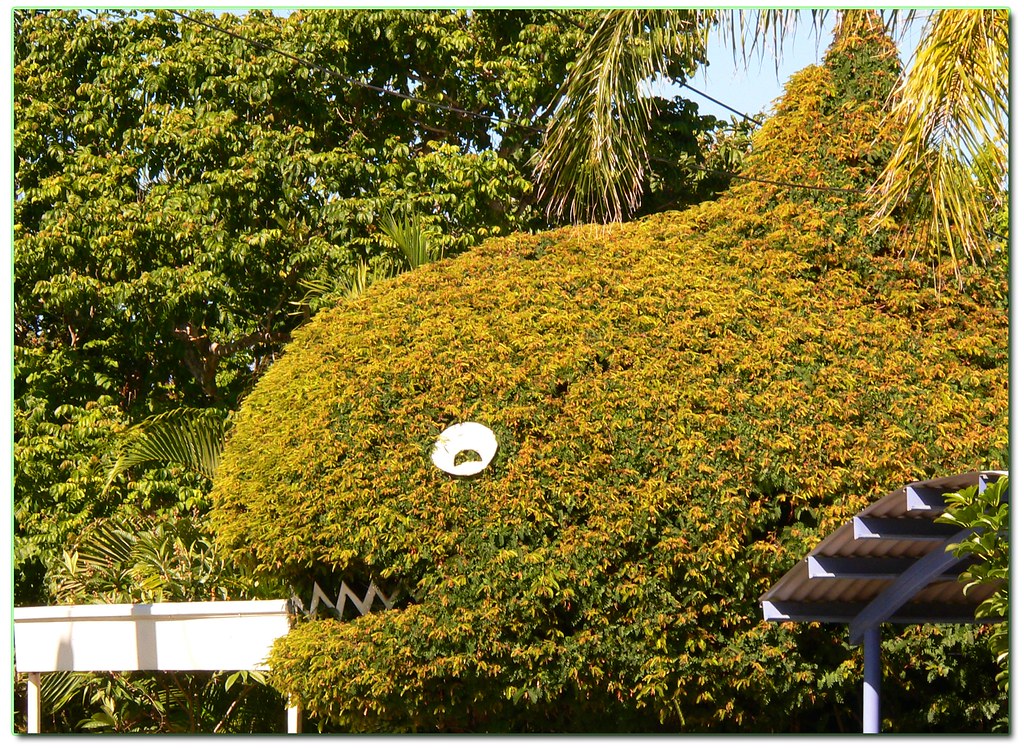

| Something fishy going on with this hedge Photo courtesy of Len Matthews |

The study also details the effect of cold weather on the hedging plants, particularly due to the winter of 1962-63, which if my secondary research is accurate, reached an official low temperature of -5 degrees Fahrenheit in Knoxville (where the study took place).

The winter hardiness research showed that plants like Ilex vomitoria (Yaupon Holly) suffered hardly any damage, which is interesting since most sources only list Yaupon as being hardy to zone 7. (In other words, it should have suffered major damage below zero degrees Fahrenheit, but apparently it did not.)

On the other hand, the cold winter apparently killed Lagerstroemia indica (Crape Myrtle) to the ground, which was not surprising. What was surprising was that it also reportedly killed Pyracantha crenato-serrata (Firethorn) to the ground.

Now Pyracantha is not used much today around Middle Tennessee, probably due to those vicious thorns. To give you an idea of its relative popularity, I'd say more than 50% of the houses in my neighborhood have crape myrtles on their property (and yes, many of those did suffer major damage due to the -2 Fahrenheit temperatures we encountered last winter, particularly the crapes that had been pruned back), whereas I've seen a grand total of one property with a few Pyrcanthas (looking glorious laden with berries) by the front foundation.

But I don't think Pyrcacanthas fell out of favor due to lack of reputed cold hardiness. Most sources I've seen list Pyracanthas as being hardy to zone 6 -- so they should have fared better than the Yaupons. But they didn't. That kind of first-hand scientific reports of heat and cold tolerance is invaluable.

(I should note that most Pyracanthas sold today are P. coccinea, not the P. crenato-serrata species of days. past. Perhaps coccinea has greater cold tolerance? It's hard to find much information on crenato-serrata via Google these days.)

|

| I think John Lennon had a song about hedges... Photo courtesy of NCM3 |

But what is also interesting about the 1960s guide is what it omits.

Guess how many mentions of bees?

Zero.

How about butterflies?

Zero.

Birds, moths, small mammals?

Zero.

In fact, there are no mentions of pollinators or wildlife at all. It's as though they don't exist. The concept of planting a shrub / hedge for anything other than privacy or aesthetic reasons seems to have not even crossed the minds of the authors.

(There's also no mention of invasiveness, which could explain why the guide recommends Euonymus alatus, i.e., Burning Bush, which is still sold in many nurseries today despite its reputed invasive characteristics.)

Fascinating.

Then again, the population of Tennessee in the 1960s was only a little more than half what it is today (~3.5 million Tennesseans in 1960 vs ~6.5 million Tennesseans in 2013).

My guess is that there was a LOT more open and wild space. People probably didn't feel the need to garden specifically to attract or support wildlife because it probably seemed as though most of the landscape already supported wildlife, ergo people could afford to devote their relatively small piece of the pie toward beauty or functionality (i.e., food, fuel, building materials for people).

The population of Tennessee, the United States and the planet continues to climb inexorably higher year after year. Even as human fertility rates drift lower, our demographic inertia carries us toward a planet more crowded with people with less space for all the other inhabitants.

Ergo, I believe it is incumbent upon all of us gardeners to do what we can to build and tend our gardens in a way that not only pleases our eyes and our palates, but also offers sustenance and habitat to the many creatures great and small who also call Earth home.